What is SMUNZ?#

Over the past six months, I’ve completed what I’d call three sprints worth of founder work to build a new fiscal hosting provider for New Zealand–based startups: StartMeUp.NZ Limited, or SMUNZ for short.

If you’re unfamiliar with fundholding or fiscal hosting the basic idea is: a fiscal host allows early-stage projects to receive, hold, and spend money before they’re ready (or willing) to incorporate.

In Aotearoa, there are already excellent examples of this model in action:

These collectives are doing important work, but they didn’t quite fit what our startup needed. That gap became the starting point for SMUNZ. We’re building a fiscal host optimised for early-stage experimentation, technical pilots, and founder-led initiatives — and we’ve set ourselves an ambitious goal: to support 500 startups over the next five years.

Startup Weekend Wellington#

In the lead-up to the March event last year, someone from the Python NZ community pointed me toward Startup Weekend Wellington. I wasn’t entirely sure I had the stamina to dedicate myself to a full-on weekend hackathon at the time, as I was working through a demanding contracting engagement. I’m glad I decided to go, even though I wasn’t certain until the last minute.

Following a flurry of idea validation, prototype development, design, and user-story writing that led to our winning pitch, the enthusiasm was real. We carried that energy well beyond the weekend, meeting up at the library and at the university where one of our team members was studying to build an initial prototype.

But when the conversation shifted to what we were told we needed next — lawyers, accountants, and formal incorporation — the air went out of the room. The team dispersed before we could ship even a minimally lovable product.

As we moved beyond the initial buzz, tensions started to surface. One team member who had taken on much of the design work felt they were contributing more than others and pushed for a much larger share of the equity. That instinct is understandable — especially when you focus on the visible effort that follows an initial engagement like Startup Weekend.

But what often gets missed is what comes after design. Once you move into the transition phase, designs and prototypes have to be taken on, built out, operated, and supported. Anyone familiar with ITILv4 will recognise this handoff: what’s designed must be obtained and built, then delivered and supported — usually by people who weren’t part of the original design work.

Design is important, but it isn’t 80% of the work. Ask anyone who has operated a real product in production: in hindsight, design and build often feel like 10%. The harder, longer work is delivering value to real users over time. Designers serve the people building the product; operators serve the people using it — and end users, in my experience, are far more demanding.

JJobs stalled during the design and transition phase and never made it off the drawing board — but that doesn’t mean the idea is dead. I’m reaching out to the original team with a simple proposal: let’s pick it back up, without the friction that slowed us down last time. No lawyers. No accountants. No incorporation hurdles up front. We bring back the pitch deck, dust off the solution architecture, and focus on what actually matters: validating the idea and raising seed funding.

We now have a safe, transparent place to hold funds, and I’m offering to pilot a Year of Service: SMUNZ will charge no fees during year one, and we’ll manage DNS and core infrastructure at no cost. At the end of that year, if the project has momentum and incorporation makes sense, we do it — informed by real progress rather than speculation.

SMUNZ Incorporation#

Early on, as conversations about incorporation started to surface, I began looking for alternatives. I remembered the Open Source Collective and wondered whether a similar model might work here. We were proposing a product built largely on open-source tooling, and I’ve spent much of my career supporting open-source systems — so the idea felt worth exploring.

I’d encountered OpenCollective through GitHub before but only had a vague sense of how it worked. As I dug in, it started to look promising. I reached out to Open Collective NZ (OCNZ), only to learn they were winding down and no longer accepting new collectives. They pointed me instead toward Gift Collective. I had a good conversation with them, but given our commercial motivations — even though, in my mind, helping young people into the workforce has a clear social good — we agreed it wasn’t quite the right fit.

It was around then that the name StartMeUp.NZ came to mind. Almost on impulse, I went through the incorporation steps.

It wasn’t my first time. Years earlier, I’d had a false start incorporating my own company, NIMHQ, and later a more successful incorporation of FreeGeek Michiana, a computer recycling and digital access project in my home state of Indiana. That project provided computers, internet access, and training to people who needed it, in exchange for help managing e-waste. The experience gave me a practical understanding of what incorporation enables — and what it doesn’t.

I’m no stranger to social enterprise initiatives of this kind, and I feel there’s a niche for this form of fiscal hosting in Aotearoa New Zealand — my home for the past twenty years. I’ve put together a small but amazing board of directors, and around six months ago it became clear it had to take priority over my paid consulting and DevOps work.

SMUNZ 2025 Sprint Retro#

This post serves as a retrospective on the work I’ve done to get SMUNZ off the ground, broken down into three sprints.

Most of that work begins in a private GitLab repository — a sandbox I think of as outcome engineering. The outcome SMUNZ is trying to engineer is simple to state, even if it’s hard to deliver: a strong, vibrant startup ecosystem and economy in Aotearoa New Zealand.

I don’t think of this work as “vibe coding.” I think of it as code staging. It’s a deliberately messy space, full of half-formed ideas, discarded experiments, and rough prototypes. When something reaches a point where it’s coherent, useful, and worth sharing, it graduates into one of several public repositories.

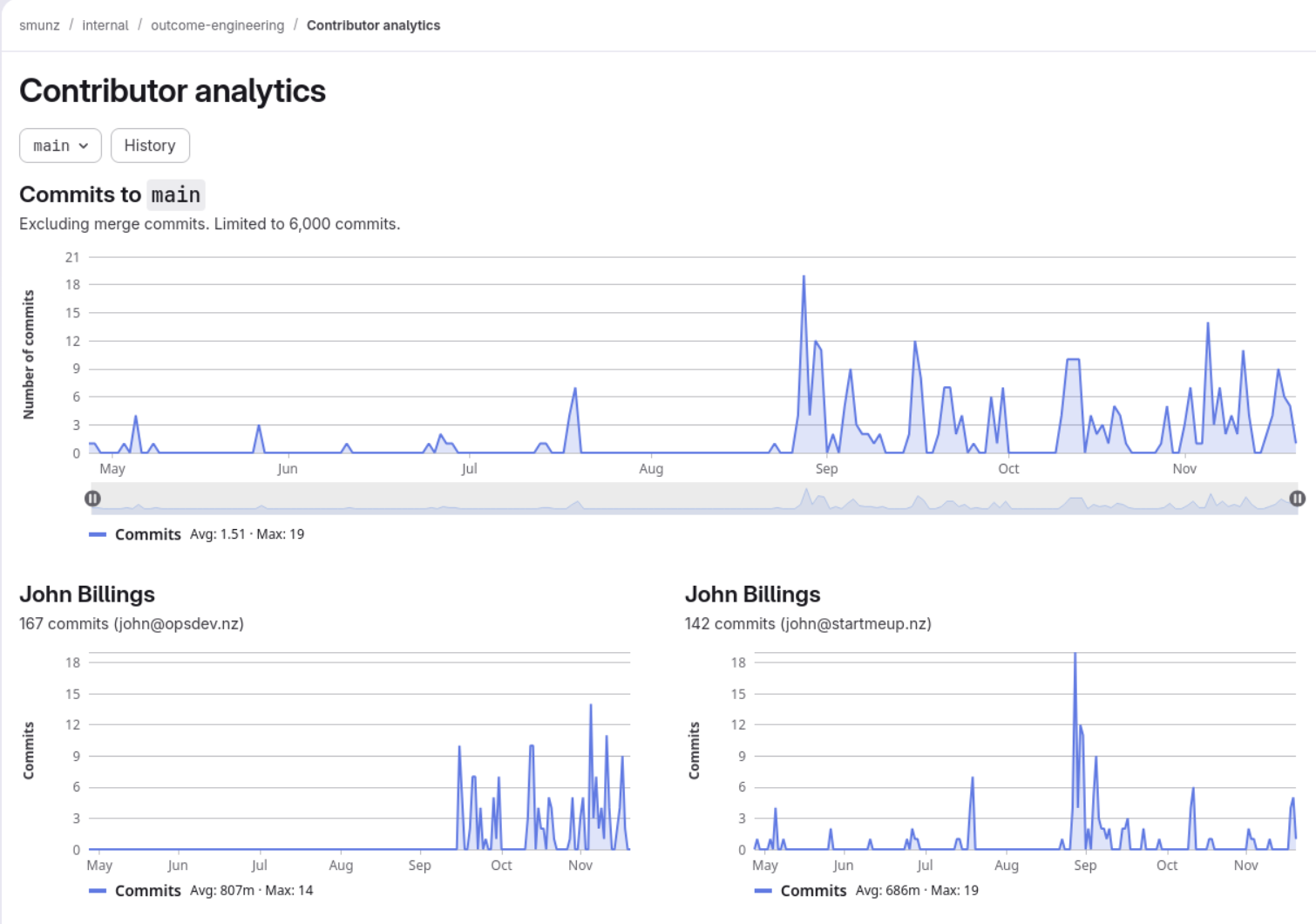

The graph below doesn’t represent every commit across all private and public repos. It shows activity from my primary skunkworks repository — where most of this early exploration and iteration happens.

I’ve been working solo for a number of years now. Before that, I collaborated with many agile teams, time-boxing incremental improvements into two-week sprints. On my own, I’ve learned that I can’t reliably produce enough meaningful deliverables to justify a traditional two-week cadence, so when I’m working solo, I operate on monthly sprints instead. That pace works better for the kind of work I’m doing here.

Rather than leaning entirely on AI agents to drive the process, I’ve effectively agentified myself. That’s not to say I don’t use AI tooling — I rely heavily on tools like Codex and Claude to help me move faster and think more clearly — but the core responsibility still sits with me.

I split that responsibility across two personas. John@StartMeUp.NZ focuses on planning, strategy, and higher-level design. John@OpsDev.NZ is responsible for delivery: turning designs into running systems and operational reality. The handover between those roles isn’t always clean, and on some days the work blends across both — which, in practice, is exactly what early-stage work often looks like.

SMUNZ Sprint #0 - Incorporation, Research and Experimentation#

My first sprint on SMUNZ stretched over several months. Between ongoing time commitments and taking some time off in August, progress was uneven. There was a period of experimentation — some “vibe coding” and more than a little wheel-spinning — before things finally started to gain traction in September. During this phase, some early design and specification work from SMUNZ was handed over to OpsDev.NZ to implement.

One of the concrete outcomes of this sprint was setting up the startmeup.nz website using the Hugo static site generator. This was very much an experiment. The first few themes we tried didn’t work well; eventually we found one that more or less worked and decided to run with it. Do I love it? Not really. In hindsight, I would have preferred a Python-based generator like Pelican, but changing it now isn’t the best use of time — that’s a problem for later.

I partially corrected that choice when setting up OpsDev.NZ as a future documentation site, and possibly the home of a future collective focused on platform engineering work. For that site, we chose MkDocs, which I’m much happier with. That decision came out of collaboration between myself and AI tooling. It’s still early days — the documentation doesn’t fully hang together yet — but it’s a start, and we’ll iterate from there.

SMUNZ Sprint #1 - DNS as Code (October/November)#

When you’re establishing an online presence, the first questions are deceptively simple: what is my domain name, and who manages my DNS? In New Zealand, we’re fortunate to have a well-supported domain ecosystem, with clear guidance on authorised .nz registrars:

Among New Zealand–based registrars, Metaname consistently rises to the top. I already had an account with them and was familiar with their service, which made it a natural choice for SMUNZ.

As I started thinking beyond a single project — toward supporting one startup now and potentially hundreds more over the next five years — manual DNS management quickly stopped being viable. That led me to OctoDNS, the tool GitHub uses to manage DNS declaratively across its domains. It’s Python-native and works in a Terraform-like way, which fits well with how I already manage infrastructure.

Metaname provides an API and an existing (though somewhat dated) Python module for managing DNS records. That was enough to get started on building a Metaname provider for OctoDNS, which became one of the concrete outputs of this sprint:

In addition to the hands-on work, I presented a talk at Kiwi PyCon in Wellington last November, where I demonstrated how OctoDNS works and used the Metaname provider to create and manage some basic DNS records in a declarative way.

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/4nitsirk/54951727037/in/photostream/

Around that time, I also became aware of another DNS management tool called Lexicon. I didn’t have time to properly evaluate it before the talk, but I’ve spent some time exploring it since. Lexicon takes a different approach: it provides an imperative, CLI-driven abstraction over the many APIs exposed by DNS providers. That’s useful in its own right, but it doesn’t offer the declarative, YAML-driven model that sits at the core of OctoDNS.

This distinction became relevant when I started a small cost-savings project involving the Namecheap registrar over the summer. Lexicon already has a provider for Namecheap, so I explored using it alongside OctoDNS. While it was possible to make the two work together — by wiring OctoDNS into a generic Lexicon provider — the result felt more like a workaround than a clean solution.

Given that experience, my likely path next year is to build a native Namecheap provider for OctoDNS, using what I learned from that initial integration. It’s more work up front, but it keeps the system declarative and consistent — which matters when you’re trying to scale DNS management across many projects.

SMUNZ Sprint #2 - Beancount#

With a working concept for DNS as Code in place and the Kiwi PyCon talk behind me, I turned my attention back to one of the harder problems for a fiscal host: how to manage money well, cheaply, and transparently.

If SMUNZ is going to provide fiscal hosting so early-stage teams can focus on their ideas instead of admin, the obvious question is whether to use established accounting platforms like Xero, MYOB, or Hnry. They’re widely used in New Zealand, familiar to accountants, and well supported — but they also come with ongoing costs that don’t sit comfortably with a model focused on minimising overhead for very early projects.

That led me to ask a more fundamental question: is there an open-source alternative that’s viable at this stage?

The tool I spent real time evaluating was Beancount — a plain-text, double-entry accounting system that treats the ledger as source code. I was aware of hledger as a similar option in this space, but Beancount stood out to me because it’s Python-based, has strong validation and reporting tooling, and fits naturally with the infrastructure-as-code approach I’ve been taking elsewhere in SMUNZ.

Beancount isn’t a drop-in replacement for Xero — and it’s not trying to be. It doesn’t provide invoicing, payroll, or a polished UI. What it does provide is a programmable, inspectable system of record — something that’s transparent, auditable, and easy to integrate with other tooling.

Beancount is now generating the report on this page:

SMUNZ Sprint #3 - OpenCollective.com Dev Environment#

At this point, the banking-to-Beancount automation is in place. I can drop bank statements for our call and current accounts into a folder, push the branch, run a few checks, and on merge to main the reconciliation happens automatically. From there, a Python script generates the financial report published on the startmeup.nz website.

What’s still missing is the OpenCollective side of the equation — which may also involve Stripe as a payment processor. That gap is now the main focus.

The path forward is reasonably clear. I’ve started work on tooling to probe, explore, and experiment with the OpenCollective API, and I’m shaping the next sprint around building out a proper development environment for that integration.

I haven’t started on Stripe yet — in fact, I haven’t really thought about it in any depth — so that’s work I’ll need to plan and tackle in a subsequent sprint once the OpenCollective pieces are better understood.

Business Planning#

I’ve deliberately pushed more formal business planning out to Q2 2026. My focus in the near term is on delivering the reconciliation automation and proving the operational model. Once that’s in place and running reliably, I’ll be looking to hand the reins over to someone else and shift into a more advisory role.

Exit Plan (and an Invitation)#

Right now, I’m the person holding the vision for what SMUNZ could become. That vision isn’t entirely original — it’s shaped by people and projects I’ve learned from over a long career — but I do believe there’s a real niche here. I’ve done some validation, I can see the shape of the problem, and I’m convinced it’s worth pursuing.

Our goal is to support 500 startups over the next five years. To get there, we’ll start small. In the coming year, I’m looking to support one collective, piloting both the onboaRrding and offboarding processes end to end.

That sets the first, and simplest, onboarding criterion for SMUNZ:

You want to build a business, but you’re not yet sure it’s the right time to incorporate.

If you’ve got an idea, but the legal, financial, and administrative overhead has been enough to slow you down — there is another way to get started. You can focus on building the product first, and incorporate later, when it actually makes sense.

We’re not saying don’t incorporate. We’re not saying don’t use Xero.

We’re just saying: don’t start there.

Start here.

The New Zealand Startup Ecosystem#

As I head into the summer break — beaches, family barbecues, and possibly a visit to IKEA — I want to say thank you to the people and communities that helped reignite the entrepreneurial part of me.

Between Startup Weekend, the Climate Tech Ecosystems drinks at Creative HQ, and the WellyForge Christmas meetup at the start of this silly season, it’s clear to me that Aotearoa New Zealand already has a strong, welcoming, and vibrant startup ecosystem. I’m not here to reinvent it — I’m here to find my Tūrangawaewae within it.

I’m looking forward to working with you all next year.